So listen to two mothers speaking motherese - the universal language we use when we talk to kids - first in English and then in Japanese. The first is that the babies are listening intently to us, and they're taking statistics as they listen to us talk - they're taking statistics. This is the critical period for sound development, but what's going on up there? So there are two things going on. So the question is, what's happening during this critical two-month period?

The babies in the United States are getting a lot better, babies in Japan are getting a lot worse, but both of those groups of babies are preparing for exactly the language that they are going to learn. Two months later something incredible occurs. So at six to eight months the babies are totally equivalent. What you see here is performance on that head turn task for babies tested in Tokyo and the United States, here in Seattle, as they listened to "ra" and "la" - sounds important to English, but not to Japanese. So the question arises, when do those citizens of the world turn into the language-bound listeners that we are? And the answer: before their first birthdays. We can discriminate the sounds of our own language, but not those of foreign languages. And that's remarkable because you and I can't do that. Well, babies all over the world are what I like to describe as citizens of the world they can discriminate all the sounds of all languages, no matter what country we're testing and what language we're using. If they do so at the appropriate time, the black box lights up and a panda bear pounds a drum. The baby sits on a parent's lap, and we train them to turn their heads when a sound changes - like from "ah" to "ee". So we've been studying the babies using a technique that we're using all over the world and the sounds of all languages. We think by studying how the sounds are learned, we'll have a model for the rest of language, and perhaps for critical periods that may exist in childhood for social, emotional and cognitive development. Work in my lab is focused on the first critical period in development - and that is the period in which babies try to master which sounds are used in their language. No scientists dispute this curve, but laboratories all over the world are trying to figure out why it works this way. Babies and children are geniuses until they turn seven, and then there's a systematic decline. (Laughter) And you'll see on the vertical your skill at acquiring a second language. The way to read this slide is to look at your age on the horizontal axis. What we see here is that language has a critical period for learning. Why is it that you can't preserve a language by speaking to you and I, to the adults? Well, it's got to do with your brain.

What this mother - and the 800 people who speak Koro in the world - understand that, to preserve this language, they need to speak it to the babies. What we see here is a mother in India, and she's speaking Koro, which is a newly-discovered language.Īnd she's talking to her baby. And what we're learning is going to shed some light on what the romantic writers and poets described as the "celestial openness" of the child's mind. The modern tools of neuroscience are demonstrating to us that what's going on up there is nothing short of rocket science. But today I'm going to talk to you about something you can't see, what's going on up in that little brain of hers.

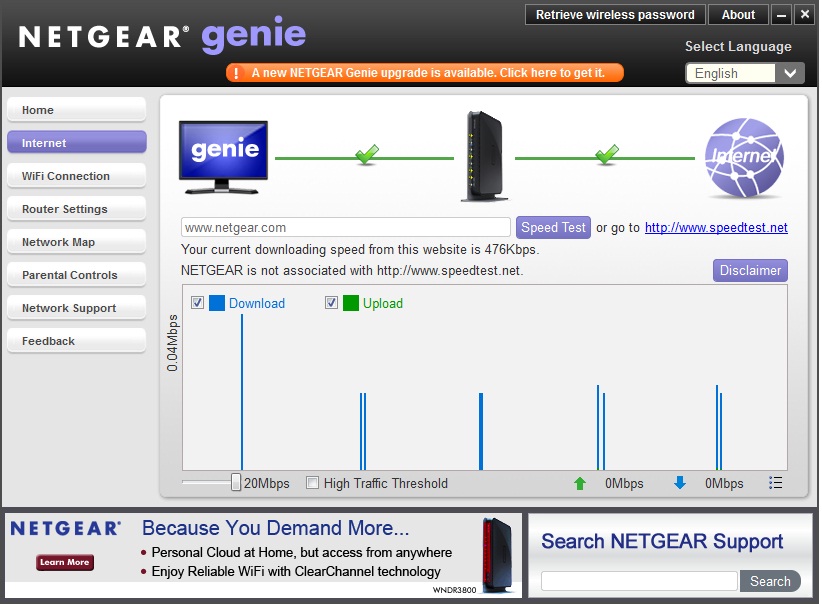

#DOWNLOAD NETGEAR GENIE SKIN#

What you're drawn to are her eyes and the skin you love to touch. Patricia Kuhl: The linguistic genius of babies

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)